Seventh Philharmonic Society Concert

London: Hanover Square Rooms—Time: Evening, Eight o’Clock

Subscription Concert: 4 Guineas

Programme

| Part I | ||

| Symphony No.3 in E flat major, Eroica | Beethoven | |

| Cavatina, ‘Come lieto a questo seno’ | Signor Ivanoff | Pacini |

| Harp Fantasia | Mlle Berthand | Berthand |

| From Der Berggeist: Duet, ‘Calma, o bella’ | Mme Stockhausen, Mr. Phillips | Spohr |

| Overture, Der Berggeist | Spohr | |

| Part II | ||

| Symphony No.4 in A major | Mendelssohn | |

| From Guglielmo Tell: Duet, ‘Non fuggir’ | Signor Ivanoff, Mr. Phillips | Rossini |

| Violin, Air varié | Monsieur Vieuxtemps | De Beriot |

| From Faust: Scene, ‘Si lo sento’ | Mme Stockahusen | Sporh |

| Overture, Fidelio | Beethoven |

| Principal Vocalists: Mme Stockhausen; Mr. Phillips, Monsieur Vieuxtemps, Signor Ivanoff | ||

| Principal Instrumentalists: Mlle Berthand; Mr. Moscheles | ||

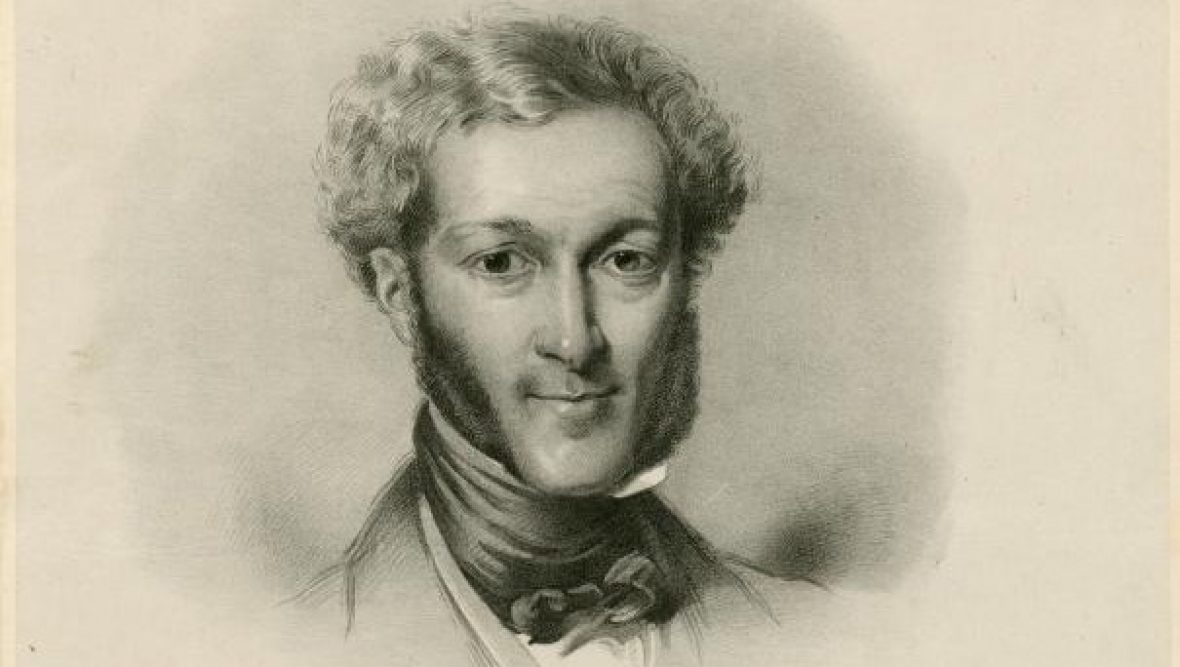

| Leader: Mr. Franz Cramer; Conductor: Mr. Ignaz Moscheles |

———————————

Encore: Cavatina, ‘Come lieto a questo seno’—Signor Ivanoff—Pacini

Salary: £21 for two performances.

[GB-Lbl RPS MS 299, f22 v.]

Advertisements

The Morning Post (June 2, 1834): 3.

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY.

The following is the programme for this evening:—

| Sym. Eroica……………………………………………………………………. | BEETHOVEN. |

| Overture to Fidelio…………………………………………………………. | DITTO. |

| Sym. In A, No. 175………………………………………………………… | MENDELSSOHN. |

| Overture to the Bergeist…………………………………………………… | SPOHR. |

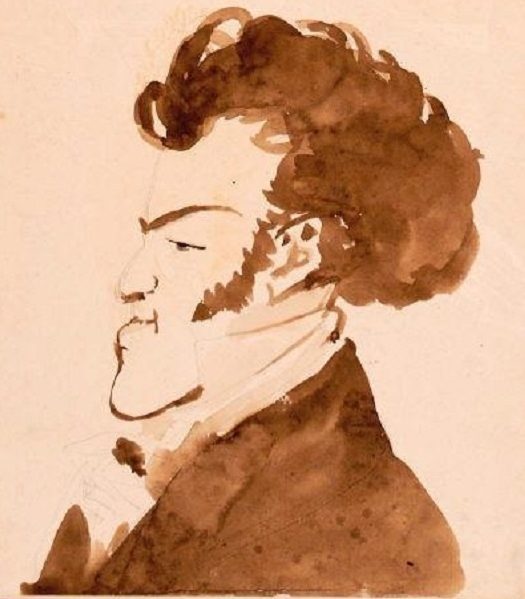

At the rehearsal on Saturday considerable interest was excited by the performance of Mdlle. BERTRAND on the harp; and a young Belgian, fourteen years of age, a pupil of M. BERIOT, on the violin. In addition to this attraction Madame STOCKHAUSEN, M. IVANOFF, and Mr. H. PHILLIPS.

Philharmonic Society Programme

UNDER THE IMMEDIATE PATRONAGE OF

Their Majesties.

————————

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY.

————————

SEVENTH CONCERT, MONDAY, JUNE 2, 1834.

ACT I.

————————

| Sinfonia, Eroica – – – – – | Beethoven. |

| Aria, M. IVANHOFF, “Come lieto” – – – | Pacini. |

| Fantasia, Harp, Mdlle. BERTRAND – – – | Bertrand. |

| Duetto, Madame STOCKHAUSEN and Mr. PHILLIPS, | |

| “Calma, o bella” (Der Berggeist) – – – | Spohr. |

| Overture, Der Berggeist – – – – | Spohr. |

ACT II.

| Sinfonia in A – – – – – | F. Mendelssohn Bartholdy. | ||

| Duetto, M. IVANHOFF and Mr PHILLIPS “Non fuggir” | |||

| (Guglielmo Tell) – – – – | Rossini. | ||

| Air varié, Violin, M. VIEUXTEMPS – – – | De Beriot. | ||

| Scena, Madame STOCKHAUSEN “Si lo sento” (Faust) – | Spohr. | ||

| Overture, Fidelio – – – – | Beethoven | ||

| Leader, Mr F. CRAMER—Conductor, Mr MOSCHELES. | |||

—————————

*** TO COMMENCE AT EIGHT O’CLOCK PRECISELY.

—————————

The Subscribers are most earnestly entreated to observe, that the Tickets are not transferable,

and that any violation of this rule will incur a total forfeiture of the subscription.

THE LAST CONCERT WILL BE ON THE SIXTEENTH OF JUNE.

Reviews

The Athenæum (June 7, 1834): 435.

The Seventh Philharmonic Concert was decidedly the best meeting of the season. Beethoven’s sinfonia ‘Eroica,’ with its sublime slow movement, and Mendelssohn’s sinfonia in A, were treats of the highest possible order, and executed in first-rate style. Madame Stockhausen, Ivanoff, and Phillips, seemed resolved that the vocal part of the performance should not be eclipsed by the instrumental—the lady sang the recitative to Spohr’s splendid ‘Si lo sento,’ with a degree of energy which surprised us, and Ivanoff’s delicious voice told well in the duet from ‘Guillaume Tell.’ The solos were a harp fantasia by Madame Bertrand; she is a spirited, sound player, with abundance of execution, and a firmness of finger not very common to artistes on that instrument—and an air varié for the violin, by De Beriot, performed by a Mons. (or Master) Vieuxtemps, who, we are told, is only thirteen—his playing was really so extraordinary, and so little like that of the generality of prodigies, that we should like to have evoked Corelli’s ghost to hear him. We do not think that the excellent Arcangelo would have ever slept quietly in his tomb again!

The Morning Post (June 6): 3

The Seventh Philharmonic Concert took place on Monday last.

PROGRAMME.

| ACT I. | ||

| Sinfonia, Eroica……………………………………. | BEETHOVEN | |

| Aria, M. Ivanhoff, “Come lieto”…………………… | PACINI. | |

| Fantasia, Harp, Mdlle. BERTRAND……………… | BERTRAND. | |

| Duetto, Madame STOCKHAUSEN and Mr. PHIL- | ||

| LIPS, “Calma, o bella” (Der Berggeist)……….. | SPOHR. | |

| Overture, Der Berggeist…………………………… | SPOHR. | |

| ACT II. | ||

| Sinfonia in A……………………………………… | F. MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY. | |

| Duetto, M. IVANHOFF and Mr. PHILLIPS, “Non | ||

| fuggir”, (Guglielmo Tell)……………………….. | ROSSINI. | |

| Air varié, Violin, M. VIEUXTEMPS………………. | DE BERIOT. | |

| Scena, Madame STOCKHAUSEN, “Si lo sento,” | SPOHR. | |

| (Faust) …………………………………………… | ||

| Overture, Fidelio……………………………………. | BEETHOVEN | |

The first allegro and Marcia funebre, the two best movements in the Eroica Sinfonia, were most effectively executed. The minuet was much too slow, as was also the andante occurring in the vivace; nor was the transition to the presto very satisfactory; for these faults we hold the conductor responsible. The aria was encored: it was sung in a correct style, and the beautiful tones of IVANOFF’S voice were generally admired.

The harp fantasia, which consisted of a well-known thema, God save the Emperor, with variations, was much applauded, and the Lady apparently much satisfied with her reception.

The most extraordinary feature of the Concert, nay, of the season, was the finished performance of Master VIEUXTEMPS, a Belgian youth, only thirteen years old. We have often been delighted and astonished with precocious talent, but it is only justice to say nothing we have heard has approached the perfection of DE BERIOT so near as the playing of this remarkable youth. Could we pay him a better compliment? We are afraid he has come too late in the season to reap much profit, yet his visit is opportune for the caterers of novelty and excellence for the provincial festivals. The applause of the audience and band was quite enthusiastic.

The Spectator (June 7): 539-540.

THE PHILHARMONIC CONCERTS.

WE tender the Directors our best thanks for the admirable concert on Monday night; theirs has been the shame of failure, be theirs, also, the glory of success. We shall notice the blemishes as they pass, but they were few and unimportant; and no English musician could attend the performance of Monday night, without a deep sense of obligation to the men whose talent and industry has familiarized their countrymen with the conceptions of BEETHOVEN and SPOHR, and enabled there thus to partake, in the highest degree, of a gratification which, not thirty years since, was exclusively confined to the Continent. This revolution has been effected, solely and entirely, by a set of English professors; they have received no support from fashion, and the patronage of royalty, so ostentatiously proclaimed in every concert bill, is a mare name. Kings, queens, princes, and lords, are not frequenters .of these concerts, which exist in their despite, and not through their agency. No matter: their places are supplied by more accurate judges and more attentive auditors.

SEVENTH CONCERT—MONDAY, JUNE 2.

ACT I.

| Sinfonia, Eroica………………………………………………….. | BEETHOVEN |

| Aria, M. Ivanhoff, “Come lieto”………………………………… | PACINI. |

| Fantasia, Harp, Mademoiselle BERTRAND……………………. | BERTRAND. |

| Duetto, Madame STOCKHAUSEN and Mr. PHILLIPS, “Calma, | |

| o bella” Der Berggeist………………………………………… | SPOHR. |

| Overture, Der Berggeist…………………………………………. | SPOHR. |

ACT II.

| Sinfonia in A………………………………………F. MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDYBEETHOVEN. | |

| Duetto, M. IVANHOFF and Mr. PHILLIPS, “Non faggir,” | |

| Guglielmo Tell…………………………………………………. | ROSSINI. |

| Air varié, Violin, M. VIEUXTEMPS……………………………. | DE BERIOT. |

| Scena, Madame STOCKHAUSEN, “Si lo sento,” Faust………… | SPOHR. |

| Overture, Fidelio…………………………………….……………. | BEETHOVEN |

| Leader, Mr. F. CRAMER; Conductor, Mr. MOSCHELES. | |

The Sinfonia Eroica of BEETHOVEN is full of its author’s peculiarities, and with his ardent and indiscriminate admirers is an especial favourite. At the risk of being branded as heretics, we dissent from this opinion. An instrumental piece lasting fifty minutes draws too largely upon the patience of any auditory, except they be able (which we confess we are not) to follow the composer in his entire design. Wonder is excited throughout, but it is not always coupled with enjoyment; we are unable to track him through the regions of fancy in which he pursues his adventurous course. This, perhaps, is our misfortune; but we can only speak of music as it excites and moves us; like Mungo in the Padlock, we desire to understand as well as to hear. The author says of this Sinfonia, that it was “composta per celebrare la morte d’ un Eroe;” but in the Marcia Funebre alone are we able to trace the accomplishment of his purpose: and here, indeed, the mighty power of his art is acknowledged—a deep and solemn feeling of interest diffuses itself over the mind, and the movement, spite of its length, never loses this influence from first to last. The Scherzo is not in keeping with the tone of the march, beautiful and original as it is; and we would gladly have terminated the composition with the latter.

SPOHR’S Overture to Der Berggeist is a finer effort of imagination than that to his Faust. He completely accomplishes his purpose of transporting you at once into the world of imagination, and prepares you for entering with him the regions of the Mountain Spirit.

In MENDELSSOHN’S Sinfonia, the orchestra being more at ease than at the first trial last year, its joyous and exhilarating character was more powerfully developed. It keeps you, throughout, in a state of excitement; just as in one of its author’s marvellous extempore performances, where the hearer listens in breathless astonishment and delight at the boundless profusion and originality of his ideas. The two Sinfonias of this evening ought to suggest to the musical student the importance of a close and diligent study of the works of the great old masters. Here we trace, in portions of each, the familiarity of BEETHOVEN and MENDELSSOHN with the compositions of SEBASTIAN BACH, and in the latter his acquaintance with those of ALESSANDRO SCARLATTI. “Invention,” said Sir JOSHUA REYNOLDS, “is one of the great marks of genius; but if we consult experience, we shall find that it is by being conversant with the inventions of others, that we learn to invent: as by reading the thoughts of others we learn to think.” Nor need we be under any apprehension that genius will be fettered by this process, or intellectual energy be wholly subjected to the restraint of the lex scripta. The fountain of nature is inexhaustible; but study and experience must direct us how to obtain and how to use its resources.

It would be a safe, though it might seem a severe rule, never to admit a Harp Concerto into these concerts. No music but of first-rate character should be introduced; and of this the harp is incapable. It is a pleasing instrument, for a short time, in the drawing-room; but out of its place in a concert of high pretension. Mademoiselle BERTRAND has great command over it; and judiciously played but a short fantasia. No one was tired, and perhaps some were pleased. But the most extraordinary effort was the Violin Solo. After the announcement in the scheme, we were surprised to see an awkward-looking boy make his appearance in the orchestra, and still more amazed to hear DE BERIOT’S well-known air with variations in E, played with the most finished and masterly execution. For strength of tone, for purity of style, for delicacy of expression, this Belgian lad approaches his unrivalled countryman and instructer [sic]. It was not merely an extraordinary exhibition for a boy, but a masterly display of fine playing, such as many a veteran performer would listen to with wonder and envy. Master VIEUXTEMPS was greeted at the conclusion of his fantasia with the loud and unanimous applause of the audience and the orchestra.

The best Vocal piece (intrinsically the best, as well as the best sung) was SPOHR’S splendid song from Faust. If Madame STOCKHAUSEN sometimes wanted the energy which Mrs. WOOD) used to infuse into this recitative and air, her singing was more pure, and more equally good. In the Duet from Der Berggetst, neither of the singers succeeded in portraying the situation in which each is placed—perhaps for want of physical power. The Duet “Non fuggir” (the version of which best known in this country begins “Dove vai”) is a fine specimen of dramatic dialogue, and a splendid effort of ROSSINI’S genius; but its power was not developed by the singers, and the audience received it very coldly. IVANHOFF’S song was mere trash.

The Atlas (June 8, 1834): 364.

Philharmonic Society—Seventh Concert, Monday, June 2.

ACT I.—Sinfonia, Eroica—BEETHOVEN. Aria, M. IVANHOFF, “Come lieto”—PACINI. Fantasia, Harp, Mdlle. BERTRAND—BERTRAND. Duetto, Madame STOCKHAUSEN and Mr. PHILLIPS, “Calma, o bella” (Der Berggeist)—SPOHR. Overture (Der Berggeist, [sic]—SPOHR.

ACT II.—Sinfonia in A—F. MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY. Duetto, M. IVANHOFF and Mr. PHILLIPS, “Non Fuggir” (Guglielmo Tell)—ROSSINI. Air varié, Violin, M. VIEUXTEMPS—DE BERIOT. Scena, Madame STOCKHAUSEN, “Si io sento” (Faust)—SPOHR. Overture (Fidelio)—BEETHOVEN.

Leader, Mr. F. CRAMER—Conductor, Mr. MOSCHELES.

BEETHOVEN’S symphonies, directed by MOSCHELES, become new compositions: neither the time nor the style in which he conceives them agrees with the traditions of the Philharmonic Society, of whom he has but lately been enrolled a member, and later still a conductor. However, that the time given by MOSCHELES is the true one—derived from a perfect intimacy with the works themselves, and knowledge of the intentions of their author—must be evident to all who compare the effects of the same piece of music played by the same band under his direction and that of others. Whether the musicians play better from having their eye directed to a man of genius as the centre of their operations, or whether they feel themselves in some measure affected by the same interest in the compositions as he evidently feels, certain it is that the hearers of the Philharmonic concert might esteem themselves fortunate if, whenever a great work of BEETHOVEN is performed, there were no other conductor than MOSCHELES. After what we have remarked, it will be needless to say anything on the excellent performance of the Sinfonia Eroica, the most various, and perhaps the most exalted of BEETHOVEN’S works—conceived in the empyrean of fancy, yet with such method that it is impossible to imagine a truer picture of a triumphantly successful life and an honourable death. The heroes to whom the sentimental abstractions of such music should be consecrated are, we hope, not warriors; but those who have left the world so much matter for grateful recollection as BEETHOVEN and MOZART.

How much is it to be regretted that a singer like IVANHOFF should be thrown away upon the modern opera! A voice, the most delicately beautiful, an intonation of the purest kind, and a natural perception of elegance which is discernible beneath all the trash of music which he usually sings, make us the more lament the school in which he is formed. It would appear as if that sensibility which is compounded in the true singer’s nature, would of itself secure for the service of the good masters and their compositions the voices of all who are rarely and exquisitely organized as singers: but no—the force of education wants not a stronger commentary (as may be observed in no unfrequent [sic] instances) than the sight of men who are formed to enter into the spirit of MOZART, HANDEL, and BEETHOVEN, deliberately preferring PACINI. Had IVANOFF’S fate driven him to England instead of to Paris, and if, instead of cultivating that finesse of execution, and that mannered style, which pass in the fashionable concert-room, and soirée for the perfection of singing, he had taken his model from the traditions of the Harrisonian school in England, what an Acis might we not have had! How we would have embodied the poetical idea of HANDEL and GAY!—and what admirable effect the almost effeminate beauty of his voice would have given to the recitative, “Help, Galatea! Help, ye parent gods!” Paris has had IVANHOFF, and what has it done with him? Instead of a singer which ought always to be heard with delight and respect, it sends him over here a copy of RUBINI, translated into Russian, castigated, and so far certainly improved, but still the imitator of a style of very questionable merit. In all that respects the mechanism of singing, Paris appears to be an excellent school—but enough is not done there to enlarge and improve the taste. The duet, “Calma, o bella,” was very nicely executed. Madame STOCKHAUSEN took the difficult distances and chromatic intervals of her part with great accuracy; and Mr. PHILLIPS was in unusually excellent voice. The overture to Der Berggeist is, in the concert-room, one of the most effective of SPOHR’S overtures—compositions which, compared with the imaginative character and the brilliant instrumentation of WEBER’S productions in the like class, do not certainly show here to great advantage, notwithstanding they often (as in the case of Der Berggeist) appear to be dramatically constructed. The one blemish which more or less runs through all SPOHR’S productions—his mannerism shown in the love of particular modulations, cadences, and in a favourite style of harmonizing—a mannerism which interferes with the entire novelty of impression in almost every fresh production of SPOHR, is the grand impediment to the complete success of one who, at intervals, comes nearer MOZART than any author of modern times. MOZART and BEETHOVEN are distinguished by the Protean variety of their forms—we recognise them not by their sounds, but by our own impressions.

Of MENDELSSOHN’S symphony we still continue to think, that the best parts are the slow movement in D minor and the minuet and trio—the former, exquisite. The first and last movements appear in the light of extremely clever writing, but they leave the hearer cold. They appeal to the head rather than the heart. As a fine symphony is nothing if not a work of passion, the pulse of the feelings is no unsafe criterion of excellence, were there no other guide to opinion. We wish that ROSSINI had written many duets as beautiful as the “Non fuggir” of William Tell. The combination of the voices of IVANHOFF and H. PHILLIPS in this music was extremely delightful.

M. VIEUXTEMPS, a lad of apparently thirteen or fourteen years of age, we believe from the Conservatorio of Brussels, and a pupil of DE BERIOT, exhibited an instance of early maturity on the violin which was truly astonishing. He is incomparably the finest boy player than we ever heard; and to attain his fine tone, perfect intonation in every part of the finger-board, rapid and distinct execution, command of the bow, and excellent taste, we should have deemed, at such tender years, absolutely impossible, did not the evidence of the fact stand before us in the unassuming shape of the little VIEUXTEMPS. May he have the career with him the most hearty good will, and were so well satisfied with what he is, that they gave him credit for what he is to be. A MORI at twelve years old is certainly entitled to consideration, as a DE BERIOT, if not a PAGANINI, in prospect.

Madame STOCKHAUSEN sang “Sio io sento” well, but not so well as we have heard it sung by Mrs. WOOD. Madame STOCKHAUSEN is, in dramatic and every other species of classical music, not remarkable for purity of taste; she is apt to alter and insert much, which though it may serve to display her vocal facility, is any thing but favourable to the composition. This is the more to be lamented, as she is in many respects well formed to please as a singer. The band accompanied this in the usual way in which they accompany the vocal pieces with which they are not acquainted—that is to say, very badly. In the recitative, they seemed hardly to know when to come in, until Mr. MOSCHELES had led off the passage on the piano-forte—a plan of performance which necessity may cause to be tolerated, but which, in any other case, must be confessed abominable. The rehearsals of the rich Philharmonic Society must be scandalously unconscientious when such a necessity exists. What do the musicians meet for on Saturday’s but to learn to perform their music on Mondays in a manner which good taste must approve? The motive of the meeting, however, is forgotten. Instead of trying the different things, until they go right, many are passed over without rehearsal at all; and the admission of the director’s friends and others on these occasions has diverted the business of the rehearsal from its proper object so fat that it is now merely a morning musical lounge. They suffer the music to go well or ill, as it may happen, careful only to avoid trouble.

Supplement to the Musical Library (July 1834): 43-44.

THE PHILHARMONIC.

SEVENTH CONCERT, MONDAY, June 2d

| ACT I. | |

| Sinfonia Eroica. . . . . . | BEETHOVEN. |

| Aria. ‘Come lieto.’ M. Ivanhoff. . . . . | PACINI. |

| Fantasia. Harp. Made. Bertrand. . . . | BERTRAND. |

| Duetto, ‘Calma, o bella.’ Madame Stockhausen and Mr. Phillips (Der | MOSCHELES. |

| Berggeist.) . . . . | SPOHR. |

| Overture. (Der Berggeist) . . . . | SPOHR. |

| ACT II. | |

| Sinfonia in A . . . . F. MENDELSSOH BARTHOLDY. | |

| Duetto. ‘Non fuggir.’ M. Ivanhoff and Mr. Phillips. (Guglielmo | |

| Tell.) . . . . . . | ROSSINI. |

| Air varié. Violin, M. Vieuxtemps. . . . | DE BERIOT. |

| Scena, ‘Si lo sento.’ Madame Stockhausen. (Faust.) . . | SPOHR. |

| Overture, (Fidelio.) . . . . . | BEETHOVEN. |

| Leader, Mr. F. CRAMER.—Conductor, Mr. MOSCHELES. | |

Beethoven’s Symphony, written, he tells us, to celebrate the death of a hero—(“composta per celebrare la morte d’un Eroe”)—has nothing in it, according to notions generally entertained, of the funereal or sorrowful character, except the march. Rather the contrary, for the scherzo, the trio, and the finale exhibit a vivacity almost amounting to playfulness; and even the first movement is far from grave. But Beethoven never sat down to compose without intending to describe something; and, as his mind was differently constituted from that of most people it is possible, may, pretty certain, that the whole of this work is an accurate representation of some well-conceived and well connected train of ideas, however he may have differed from others in his mode of giving a musical form to them. The whole is, past all dispute, the creation of a mighty genius.

The funeral march goes deeply to the heart of all who are sensible to the effects of music. The change in this from minor to major is almost transporting; and the recurrence of the subject hardly less affecting. The scherzo hurries the hearer along with it, increasing his surprise at every bar, which does not abate during the progress of the last equally original and extraordinary movement. But certainly the symphony is long, and, with the addition of a vocal piece of a complexion quite different, is enough for one whole act. Thus it should always be given, and thus it would always be enjoyed. To follow it almost immediately by the duet and overture of Spohr, compositions of a similar cast, and emanating from nearly the same school, was extremely ill-judged, and shows how little thought is exercised, how entirely calculation is neglected, in the formation of these concert bills. But a further proof of this is given at the very beginning of the next act, where we meet with a composition—an exceedingly clever one, certainly—the merits of which are only disclosed to such as direct their attention laboriously to it, and are become familiar with it by frequent hearing. A light and comparatively simple work, one of Haydn’s earlier compositions, would have been a much better relief to Beethoven’s elaborate symphony than that of Mendelssohn, which is a study, and requires to be studied, and called for fresh exertion from the already fatigued mind which required something on which it could quietly repose.

Madame Bertrand, a French lady, first appeared publicly in England at this concert. Her tone is powerful without being harsh, and she has a full command of the instrument; but we cannot say a word in praise of the music she chose for her début: it was deplorably trifling. The wonder of the evening was a boy not yet fourteen years of age—indeed his appearance would warrant a belief that he is much younger, named Vieuxtemps, who has been brought up at the Conservatoire of Brussels, and is now a pupil of De Beriot, whose tone, taste, manner of bowing, and general style he has been so successful in acquiring, that his playing might easily be mistaken for that of his master. We cannot bestow higher praise; and, in confessing our astonishment at such greatness of talent, such execution, and, what is yet better, so much soul, together with such strength and firmness, we only acknowledge what we felt in common with every one in the room at all capable of appreciating this genuine prodigy.

M. Ivanhoff sang, very sweetly, as good a composition as Pacini is capable of producing. He also joined Mr. Phillips in one of Rossini’s finest works, to which both did the most complete justice. But it was not received with the applause that both the music and performance deserved. The duet of Spohr was not executed in so satisfactory a manner as we have witnessed. Madame Stockhausen sang the scene from Faust most correctly in every way, but she wants physical power and rather more animation to make her performance of such music perfect.