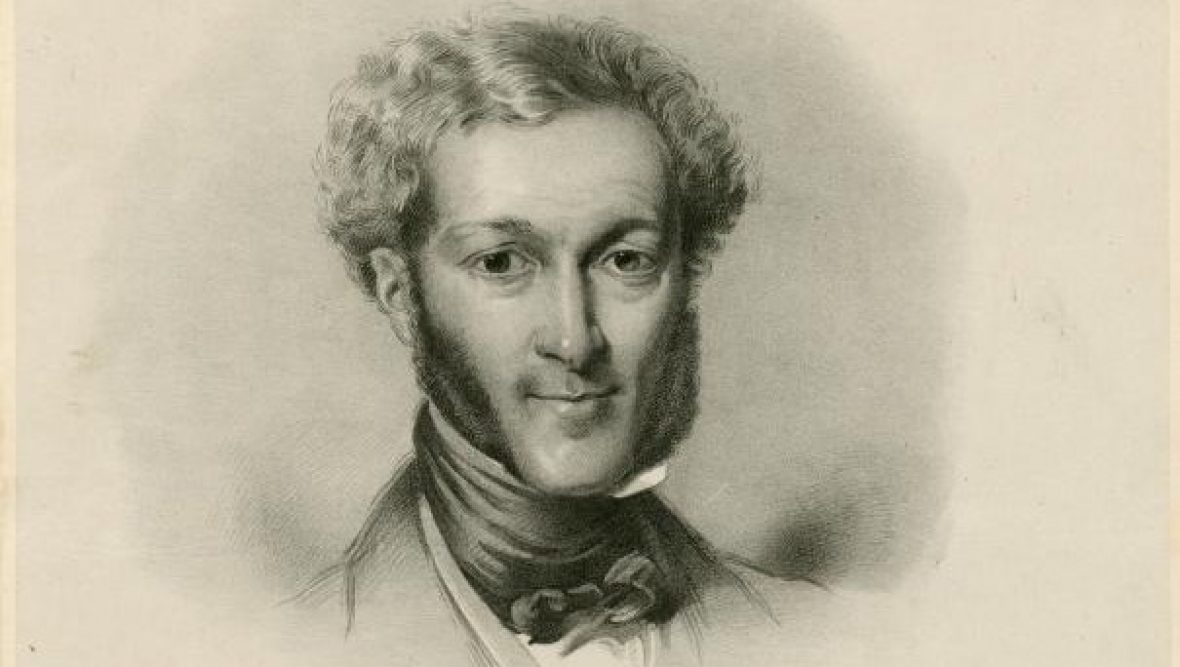

Vocal and Instrumental Concert by Louis Spohr

Paris: Académie Royale de Musique

↓Programme

| Ballet, Clari | ||

| Duet | M. Levasseur, Signor Bordogni | Rossini |

| Cavatina | Mlle Cinti | Rossini |

| Free Piano Fantasia | Mr. Moscheles | |

| Overture, Alruna | Spohr | |

| Quintet in E flat major for Piano and Wind Instruments | Messrs. Moscheles, Spohr, Habeneck, [?], [?] | Spohr |

| Violin Concerto No.9 in D minor (new) | Mr. Spohr | Spohr |

| Violin Potpourri No. 4 in B major (Op. 24) | Mr. Spohr | Spohr |

| Principal Vocalists: Mlle Cinti; M. Levasseur, Signor Bordogni |

| Principal Instrumentalists: M. Habeneck, Messrs. Moscheles, Spohr |

———————————

Programme Notes: The quintet performed might have been the Quintet in C major, Op.52

Overall receipts: 2696, 20 francs; Expenses: 1349,00 francs; Spohr’s Salary: 674,60 francs

[F-Pan: Archives Nationales AJ/13/394 IV No.6]

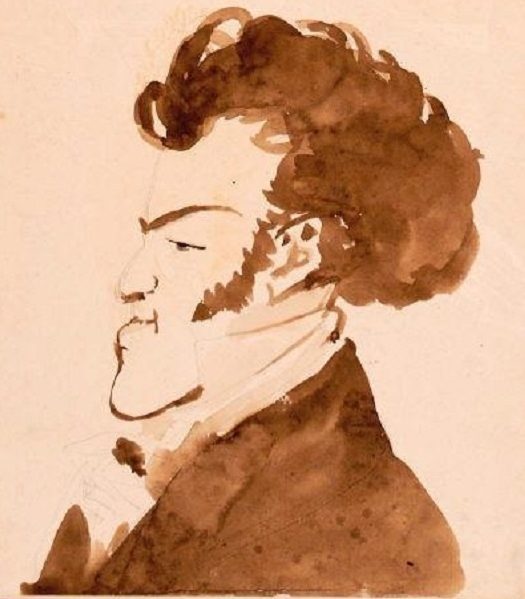

Charlotte: Spohr had entrusted Moscheles at one of his matinées with the pianoforte part of his quintet in E flat (with wind instruments), which was greatly applauded by the audience. In addition to this, Moscheles was called on to improvise, and was particularly happy to find Reicha and Kreutzer for the first time among his audience. [RMM, 26]

Spohr: The first time my wife played the piano part [Piano Quintet in E flat]; but when Moscheles subsequently requested permission to study it and to play it once, she had not the courage to play it any more in Paris, after him. He remained therefore in possession, and entered more and more into the spirit of the composition. He executed the two allegro subjects especially with far more energy and style, which certainly greatly increased their effect. As the wind instruments of Reicha’s quintet were excellent, I never recollect to have heard that quintet so perfectly rendered as then, although I have heard it played in more recent days by many celebrated pianoforte virtuosi. [Louis Spohr, Louis Spohr’s Autobiography, vol. 2, 2 vols (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1865).]

Letter: Louis Spohr to a friend.

Paris, 30 January 1821

…Seit vier Wochen ist Moscheles hier. Er erregt durch sein äußerst brillantes Spiel große Sensation, und weiß Künstler und Dilettanten für sich zu gewinnen, erstere durch den Vortrag seiner geistreichen Compositionen, letztere hauptsächlich durch seine freien Phantasien, in denen er sich dem Pariser Geschmack, so weit es ihm sein Deutschthum erlaubt, zu nähern weiß.

[Spohr, Autobiography, II, 140-141.]

Letter: Louis Spohr to Carl Friedrich Peters.

Strasbourg, 8 February 1821

….Das Clavier-Quintett hat in Paris große Sensation gemacht; wir haben es mehrere male mit Blasinstrumenten und Saiteninstrumenten gemacht und Moscheles hat es einmal in einer Gesellschaft von 250 Personen gespielt, wo es den größesten Enthusiasmus erregte.Die Clavierspieler dort haben sich angelegentlich erkundigt, ob es nicht bald erscheinen würde.

[Sächsisches Staatsarchiv, Staatsarchiv Leipzig (D-LEsta), Sign. 21070 C. F. Peters, Leipzig, N. 850, Bl. 93f.]

Letter: Louis Spohr to a friend.

Paris, 12 January 1821

With a mind greatly relieved, I write to announce to you, my dear friend, that I have made my public début and with success. It is always a hazardous undertaking for a foreign violinist to make a public appearance in Paris, as the Parisians, are possessed with the notion that they have the finest violinists in the world, and consider it almost in the light of arrogant presumption when a foreign considers he has talent sufficient to challenge a comparison with them.

I may therefore well be a little proud of the brilliant reception I met with the day before yesterday, and the more so that, with the exception of a dozen persons, the auditory was personally unknown to me, and there were non among them who had been admitted with free-tickets in purchase of their service as claqueurs. But I had prepared myself very carefully for the occasion, and was properly supported by the careful accompaniment of Mr. Habeneck. I was, however not in the least nervous, which is sometimes the case with me when I appear for the first time in a strange country, and which occurred to me the year before in London. The reason why I did not feel so in this instance, was doubtless, that here I had already played before all the most distinguished musicians, previous to my appearing in public; but in London eight days only after our arrival, without having been previously heard by any person, I was constrained to appear at the philharmonic concert.

Before I enter into any details of the concert, I must first relate how I came to give it. It is at all times a tedious business to make arrangements for a concert in any town, but in Paris, which is so extensive, where so many theatres are daily open, where there is so much competition and so many obstacles to overcome, it is indeed a Herculean task. I think also that this is the reason why so many artists who come to Paris, decline giving a public concert, which, besides being attended with the enormous expense of nearly 3000 francs, is always an undertaking of great risk. If these matters have been extremely unpleasant to me in other places, you may readily imagine how I feared to attempt them here. In order to get over the difficulty, I bethought myself of making a proposition to the directors of the grand opera, to divide with me the expenses and the receipts of an evening entertainment of which the first half should consist of a concert and the second of a ballet. Contrary to the expectation of all those to whom I had spoken on the subject, this proposition was acceded to.

The consent of the minister was however so long delayed, that the concert could not be announced till three days before it took place, and although the house was well filled, yet I ascribe to this delay that it was not so crowded as I had expected so novel and, from its novelty, so attractive an arrangement would have been for the Parisians. The half which came to my share, after deduction of the expenses, was therefore, as you may imagine, not very considerable: but as I had not calculated upon making much pecuniary gain in Paris, I do not regret this arrangement at all, as it saved me an immense deal of trouble, and yet gave me an opportunity of making my appearance in public. Of my own compositions I gave: the overture to “Alruna,” the newest violin concerto, and the potpourri on the duet from “Don Juan.” Between these a cavatine of Rossini’s was sung by Mademoiselle Cinte, and a duet, also of the same master, by Messrs. Bordogni and Levasseur. At the rehearsal the overture was repeated three times, and in the evening therefore, although it did not go off quite so well as the last time at the rehearsal, the public nevertheless could not refuse their applause of its execution. In the concerto, as well as in the potpourri, some of the wind instruments failed twice, from a negligence in observing the pauses, which seems somewhat usual with the French, but fortunately it was not much disparaged by it. The satisfaction of the audience was unmistakably expressed by loud applause and cries of Bravo! To-day, however, the criticism of the majority of the journals is not so favourable. I must solve this riddle for you. Previous to every first appearance in public, whether of a foreigner or a native, these gentlemen of the press are accustomed to receive a visit from him, to solicit a favourable judgment, and to present them most obsequiously with a few free admission tickets. Foreign artists, to escape these unpleasant visits, sometimes forward their solicitations in writing only, and the free admissions at the same time; or, as is of frequent occurrence, induce some family to whom they have brought letters of introduction, to invite the gentlemen of the press to dinner, when a more convenient opportunity is offered to give them to understand what is desirable to have said of them both before and after the concert. This may perhaps occur now and then in Germany; but I do not think, that newspaper critics can be anywhere so venal as here. I have been told that the first artists of the Théatre français, Mlle. Mars, and even Talma, pay annually considerable sums to the journals, in order to keep those gentlemen constantly in good humour, and that the latter, whenever they wish to extricate themselves from any pecuniary embarrassment, find no method so sure as to attack some esteemed artist until he submits to a tribute of money. How the opinions of a press that are so purchasable, are at all respected, I cannot understand. Suffice however to say, I did not pay any of these supplicatory visits, for I considered them unworthy of a German artist, and thought that the worst that could happen would be, that the journalists would not take any notice at all of my concert. But as these have each a free pass to every performance at the grand opera, I found I was mistaken. They all speak of it; some with unqualified praise, but the majority with a But, by which the praise is more than sufficiently diminished. In all these notices, however, French vanity speaks with the utmost self-assurance. They all begin by extolling their own artists, and their artistic culture, above all other nations; they think that the country that produced Messrs. Baillot, Lafont and Habeneck, need envy no other its violinists; and whenever the play of a foreigner has been received here with enthusiasm, it is nothing more than a proof of the great hospitality which the French in particular shew towards foreigners. Apart from this vanity the notices are very contradictory: The “Quotidienne” says, for instance: “Mr. Spohr aborde, avec une incroyable audace, les plus grandes difficultés, et l’on ne sait ce qui étonne le plus, ou son audace ou la sureté avec laquelle il exécute ces difficultés.” In the “Journal des Débats,” on the other hand: “Le concert exécuté par Mr. Spohr n’est point surchargé de difficultés,” etc. These gentlemen differ also in opinion respecting the merits or demerits of my compositions. The majority think them good, but without saying why; but “Le Courier des Spectacles,” which altogether speaks most disparagingly of me, says: “C’est une espèce de pacotille d’harmonie et d’enharmonie germaniques que Mr. Spohr apporte, en contrebande, de je ne sais quelle contrée d’Allemagne.” But Rossini is his man, of whom he says further on: “Cet Orphée moderne a défrayé de chant le concert de Mr. Spohr, et il lui suffit pour cela de prêter une petite aria et un petit duo bouffo.” But as a violinist I found more grace in his eyes; he says for instance: “Mr. Spohr comme exécutant est un homme de mérite; il a deux qualités rares et précieuses, la pureté et la justesse,” but then winds up his phrase like a true Frenchman: “s’il reste quelque temps à Paris, il pourra perfectionner son goût et retourner ensuite former celui des bons Allemands.” If the good man only knew what the “bons Allemands” think of the musical taste of the French?!

[Louis Spohr, Louis Spohr’s Autobiography, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1865), 119-123.]

Advertisement

Le Moniteur Universel (January 10, 1821): 42.

Académie royale de Musique. Auj. Concert vocal et instrumental, dans lequel on entendra M. Spohr, suivi du ballet de Clari.

Reviews

Journal de Paris (January 12, 1821): 4.

Concert de M. Spohr.

A l’époque de l’année à laquelle nous sommes parvenus, de nombreux concerts ont ordinairement été donnés, soit au théâtre Favart, sont au théâtre Louvais. Comment se fait-il donc que le concert donna par M. Spohr, musicien allemand, soit le premier, le goût pour la musique aurait-il [*] ? Non. Il fait donc en attribuer la cause à la multiplicité des [*] et des soirées musicales. De tous les côtés, au faut de la [*] [*] [*], on attirait l’affluence à l’aide de professeurs et de [*] connus. Maintenant on emploie un autre moyen : on offre de le musique au rabais ; et, dans ce siècle calculateur, ce moyen ne peut manquer de rendait. Avec le prix que conteraient deux billets d’un concert à l’Opéra, on se procure un abonnement pour six ou huit concerts particuliers. Qu’importe la qualité, c’est la quantité qui décide ces hommes dont l’esprit de hausse jusqu’à savoir que cinq et quatre font neuf.

Ces réflexions nous ont’ été inspirées en voyant la salle de l’Opéra à moitié remplie pour le concert de M. Spohr ; la réputation de ce professeur avait attiré une assemblée, sinon très-nombreuse, au moins fort en [*] de porter un jugement sain. M. Spohr connait le mécanisme de son instrument ; il joue très-bien du violon, mais il manque de cette chaleur, de ce je ne sais quoi qui portent la vie dans les arts. Il est resté froid, même en jouant dans ay air variées le joli thème du duo je Juan : Laciderem la mano. M. Spohr a tort de croire que tout le talent d’un violon réside dans la main gauche, et consiste à faire des doubles cordes : il abuse du coup d’archet, que l’on appelle Gigue : c’est un agrément dont en ne doit faire c u on usage très-modéré.

En résultat, M. Spohr est un professeur très-distingue (I); il fera grand plaisir en Allemagne et en Italie ; mais le pays qui possède MM. Baillot, Lafont en Habeneck n’a rien à envier à ses voisins.

Conversationsblatt, vol. 3, (April 7, 1821): 334.

…sein Antheil kam auf…nur 700 Franken empfangen.

Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode (May 22, 1821): 523-524.

Der berühmteste deutsche Geiger und der berühmteste deutsche Fortepianospieler (brauche ich zu sagen, daß Spohr und Moscheles hiemit gemeint sind?) haben hier Konzert gegeben. Spohr hat als Instrumentalkomponist, besonders unter den hiesigen Musikverständigen, die allgemeinste und dankbarste Anerkennung seines großen, fast möchte ich sagen, klassischen Talents gefunden; als Geiger ist ihm eine zu elegische, bloß passive Weichheit und Mangel an Effekt und Kraft, auch in der äußersten Höhe des Griffbrets ein leichter Anflug von Unreinheit vorgeworfen worden. Meine Meinung stimmt mit diesem öffentlichen Urtheile vollkommen übereilt. Den tausendfingerigen Moscheles kennt Jedermann; dieser musikalische Briareus könnte den Hamburger Korrespondenten abspielen und er würde Effekt machen.